I was given the opportunity to test AppSwitch, a network stack for containers and hybrid setups that promises to be super easy to deploy and configure, while offering outstanding performance. Sounds too good to be true? Let’s find out.

A bit of context

One of the best perks of my job at Docker has been the incredible connections that I was able to make in the industry. That’s how I met Dinesh Subhraveti, one of the original authors of Linux Containers. Dinesh gave me a sneak peek at his new project, AppSwitch.

AppSwitch abstracts the networking stack of an application, just like containers (and Docker in particular) abstract the compute dimension of the application. At first, I found this statement mysterious (what does it mean exactly?), bold (huge if true!), and exciting (because container networking is hard).

The state of container networking

There are (from my perspective) two major options today for container networking: CNM and CNI.

CNM, the Container Network Model, was introduced by Docker. It lets you create networks that are secure by default, in the sense that they are isolated from each other. A given container can belong to zero, one, or many networks. This is conceptually similar to VLANs, a technology that has been used for decades to partition and segregate Ethernet networks. CNM doesn’t require you to use overlay networks, but in practice, most CNM implementations will create multiple overlay networks.

CNI, the Container Network Interface, was designed for Kubernetes, but is also used by other orchestrators. With CNI, all containers are placed on one big flat network, and they can all communicate with each other. Isolation is a separate feature (implemented in Kubernetes with network policies.) On the other hand, this simpler model is easier to understand and implement from a sysadmin and netadmin point of view, since a straightforward implementation can be done with plain routing and CIDR subnets. That being said, a lot of CNI plugins still rely on some sort of overlay network anyway.

Both approaches have pros and cons, and if you ask your developers, your sysadmins, and your security team what to do, it can be very difficult to get everyone to agree! In particular, if you need to blend different platforms: containers and VMs, Swarm and Kubernetes, Google Cloud and Azure, …

That’s why something like AppSwitch is relevant, since it abstracts all that stuff. OK, but how?

How AppSwitch works

Or rather: how I think it works, in a simplified way.

AppSwitch intercepts all networking calls made by a process

(or group of processes). When you create a socket, AppSwitch

“sees” it. When you connect() to something, if the destination

address is known to AppSwitch, it will directly plumb the

connection where it needs to go. And it learns about servers

when they call bind().

“Intercepting network calls? Isn’t that … slow?”

No! Indeed, it would be slow if it were using standard ptrace().

But instead, it is using mechanisms that are similar

to the ones used to execute e.g. kernel performance profiling.

These mechanisms are specifically designed to have a very low

overhead.

Furthermore, AppSwitch doesn’t intercept the data path calls

(like read and write).

That means, the IO speeds are at least as good as native.

I say at least because AppSwitch may transparently shortcircuit the

network endpoints over a fast UNIX connection when possible.

“Do I need to adapt or recompile my code?”

No, you don’t need to recompile, and as far as I understand, that

works even if you’re not using the libc; and even if your

binaries are statically linked. Cool.

In practice

The exact UX for AppSwitch is not finalized yet. In the version

that I have tested, you execute your programs with a special ax

executable, conceptually similar to sudo, chroot, nsenter, etc.

A program started this way, and all its children, will be using

AppSwitch for their network stack. It is also possible to tie

AppSwitch to network namespaces or even other kind of namespaces

so that the program doesn’t have to be started with ax.

There is a demo at the end of this post, but keep in mind that the final UX may be different.

Benefits

This system has a handful of advantages. It abstracts the network stack, but it also simplifies the actual traffic on the network. In some scenarios, this is going to yield better performances. And in the long term, I believe that it will also bring subtle improvements, similar to what unikernels have done in the past (and will do in the future).

Let’s break that down quickly.

Independent of CNI, CNM, or what have you

Network mechanisms in container-land rely heavily on network namespaces. Virtual machines rely heavily on virtual NICs. AppSwitch abstracts both things away. The network API is now at the kernel level. You run Linux code? You’re good. (Windows apps are a different story, of course.)

You can connect together applications running in containers, VMs, physical machines, and it’s completely transparent.

Simpler networking stack

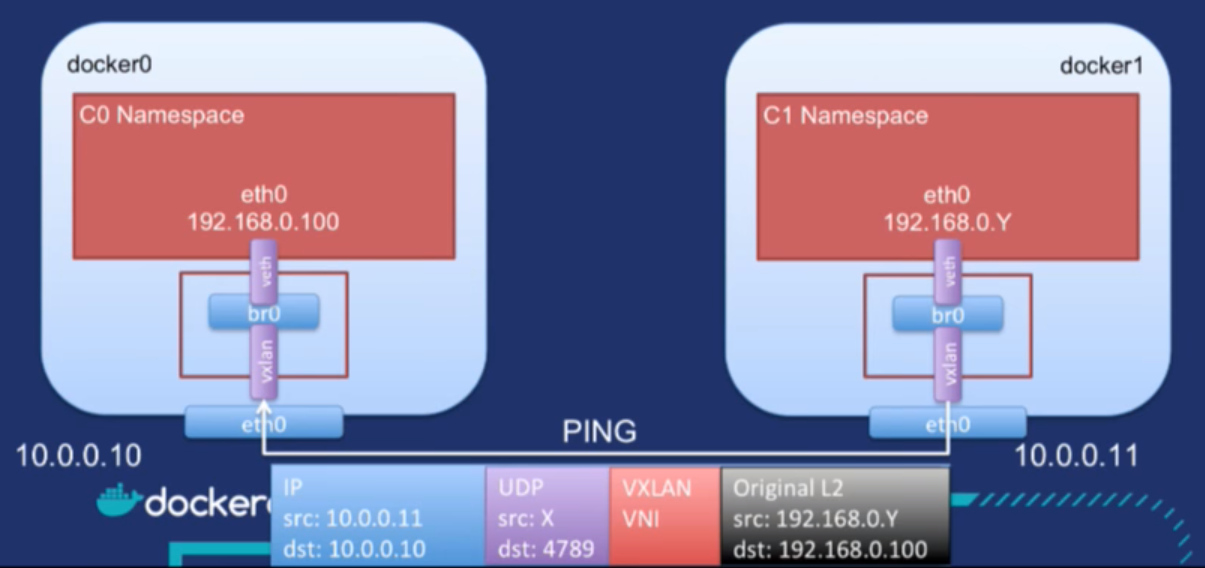

As we’ve seen in the introduction, overlay networks are very frequent in the world of containers. As a result, when a container communicates with another, we get network traffic looking like this:

(Slide from Laurent Bernaille’s presentation Deeper Dive In Overlay Networks, DockerCon Europe 2017.)

The useful payload in that diagram is within the black rectangle. Everything else is overhead. Granted, that overhead is small (a few bytes each time), which is why overlay networks aren’t that bad in practice (if they are implemented correctly). But there is also a significant operational cost, as those layers add complexity to the system, making it rigid and/or difficult to setup and operate.

AppSwitch lets us get rid of these layers, because once a connection has been identified at the socket level, we do not need any of the other identity information. It reminds me a little bit of ATM (or the more recent MPLS), where packets do not contain full information like “this is a packet from host H1 on port P1 to host H2 to port P2.” Instead, each packet carries only a short label, and that label is enough for the recipient to know which flow the packet belongs to. AppSwitch somehow seems to do this without touching the packets or even having access to them.

Faster local communication

One thing that network people like to do is to complain about the performance of the Linux bridge. The core of the issue is that the Linux bridge code was single threaded (I don’t know if that’s still the case), and this would slow down container-to-container communication (as well as anything going over a Linux bridge). There are remediations (like using Open vSwitch, for instance) but AppSwitch lets us sidestep the problem entirely.

In the special case of two containers communicating locally, the classic flow would look like this:

write() -> TCP -> IP -> veth -> bridge -> veth -> IP -> TCP -> read()

And with AppSwitch, it becomes this:

write() -> UNIX -> read()

There is not even a real IP stack in that scenario and the application doesn’t even notice it!

Demo

Alright, a little less conversation a little more action!

Remember: the exact UX of AppSwitch will probably be different, but this is what I tested looks like.

Getting started

First of all, since I wanted to understand the installation process from A to Z, I did carefully read the docs, and then I decided to reduce the instructions to the bare minimum.

First, I clone the AppSwitch repository:

git clone git@github.com:appswitch/appswitch

cd appswitch

Then, I compile the kernel module. Wait, a kernel module? As I mentioned earlier, this version of AppSwitch works by intercepting network calls at the kernel level. But I’m told that in a future version, it will be able to offer the same functionality (and performance!) without needing the kernel module.

make trap

cp trap/ax.ko ~

Next up, I copy AppSwitch userland piece. That part is written in Go, and currently recommends Go 1.8. I’m using a trick to run the build with Go 1.8, regardless of the exact version of Go on my machine:

docker run \

-v /usr/local/sbin:/go/bin \

-v $(pwd):/go/src/github.com/appswitch/appswitch \

golang:1.8 go get -v github.com/appswitch/appswitch/ax

(If you just went “WAT!” at this and are curious, you can check this other blog post for crunchy details.)

Then I copy the module and userland binary to my test cluster.

(The IP addresses of my test machines are in ~/hosts.txt, and

I use parallel-ssh to control my machines.)

tar -cf- /usr/local/sbin/ax* ~/ax.ko |

parallel-ssh -I -h ~/hosts.txt -O StrictHostKeyChecking=no \

sudo tar -C/ -xf-

We can now load the module:

parallel-ssh -h ~/hosts.txt -O StrictHostKeyChecking=no \

sudo insmod ~/ax.ko

Next, we need to run the AppSwitch daemon on our cluster. AppSwitch is structured like the early versions of Docker: the daemon and client are packaged together as one statically linked binary. There is another similarity: the daemon exposes a REST API that the client consumes.

The exact command that we need to run is highlighted below;

it boils down to running ax -daemon -service.neighbors X

where X is one (or multiple comma-separated) address of

another node. You don’t need to specify all nodes: AppSwitch

will use Serf to establish cluster

membership. I specify two nodes in the example below to

be on the safe side if one node is down for an extended

period of time.

The whole command is wrapped within a systemd unit, because why not.

parallel-ssh -I -h ~/hosts.txt sudo tee /etc/systemd/system/appswitch.service <<EOF

[Unit]

Description=AppSwitch

[Service]

ExecStart=/usr/local/sbin/ax -daemon -service.neighbors 10.0.0.1,10.0.0.2

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

EOF

Then we fire up that systemd unit:

parallel-ssh -h ~/hosts.txt sudo systemctl start appswitch

At this point, AppSwitch is running on the whole cluster. Nodes can be added and removed at will.

Basic use

To run a server through AppSwitch, I have to give it an IP identity, like this:

ax -ip 1.1.1.1 python3 -m http.server

(This command runs a static HTTP server on port 8000.)

Then, any process running through AppSwitch, on any node, can access that service by referencing that IP address:

ax curl -I 1.1.1.1:8000

HTTP/1.0 200 OK

Server: SimpleHTTP/0.6 Python/3.5.2

Date: Thu, 08 Mar 2018 03:11:11 GMT

Content-type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 623

Advanced use

AppSwitch also allows to set a name for each service, and then use that name to connect to it:

# Server

ax -name web python3 -m http.server

# Client

ax curl web:8000

It also gives us load balancing, out of the box, just by running multiple server processes with the same name or IP address identity.

There is an interesting-looking system of labels, allowing to control which clients can see/communicate with servers; but I didn’t investigate that in depth.

Performance

That part is particularly interesting. I benchmarked raw

transfers between two EC2 VMs, measured with iperf.

AppSwitch performance was so close to native performance,

that it was indistinguishable. In fact, on average, AppSwitch

was even slightly faster than native!

(On my test machines, I saw 980 Mb/s with AppSwitch and 950 Mb/s

without.) It is probably a coincidence; perhaps my VM had

a noisy neighbor during my tests.

This funny result reminded me of a VMware benchmark I saw a while ago, where Redis ran faster on a VM than on the host. This was caused (if I remember correctly) by limiting the VM to one CPU, and pinning that CPU to a physical one on the host. This would prevent the VM (and the Redis process inside) from switching CPUs (and the associated cache misses). The morale of the story is that sometimes, we get seemingly impossible results, but if we dig enough, there is a perfectly logical explanation. Perhaps there is a similar story here as well, who knows.

I also conducted tests with many small parallel requests. The

performance here was significantly lower, but when I tried to

figure out why, I noticed that systemd-journald was using up

most of the CPU on the machine. It turns out that the debug

build of AppSwitch that I’m running is pretty verbose about

what it does. At some point I’d like to do more testing, but

for now I was happy with the results.

Conclusions

With virtual machines, the interface between the VM and the rest of the world is the API with the hypervisor. It’s a small API, but it’s specific to each hypervisor, and it is very far from what our applications need.

With containers, the interface between the container and the rest of the world is the kernel syscalls ABI. It’s a much bigger API, and it’s specific to Linux. It’s also a very stable API, because each time somebody breaks it (by design or by mistake) they receive a deluge of profanity and verbal abuse.

Container engines like Docker give us a very efficient way to abstract compute resources: a container image for Linux x86_64 can run on pretty much any Linux x86_64 machine (and will eventually run at near-native speed on Windows x86_64 machines too, thanks to some pretty cool stuff happening in the Windows ecosystem.)

However, containers don’t abstract the network stack — at all.

Our applications still run in things that have (virtual) network

interfaces, and communicate by sending IP packets. When you

think about it, these things (interfaces and packets) are not

essential, and in fact, they do not exist at the kernel syscall

boundary. Most applications create sockets, connect() or bind()

them, and then read and write on file descriptors. No packets, no

interfaces.

As a result, a container connected with AppSwitch doesn’t even need to have an IP address, or even a full IP stack! That’s why AppSwitch is exciting: it offers us a way to get the features that we need, without carrying the overhead of legacy concepts — just like Docker captured exactly what was needed to abstract a runtime environment, without having to deal with concepts like a PCI bus, SCSI adapter, or APIC controller.