To help @EstelleDeau to refactor some code, I had a look at introspection and reflection features in IDL. It is a really weird language (especially when my primary languages are now Python and Go), but it was a fun ride.

Note: we are talking about Interactive Data Language here; not Interface description language. The former is a programming language used for data anlysis by e.g. NASA; the latter is used to describe component interface for e.g. RPC.

Why?

Why am I doing this?

Science!

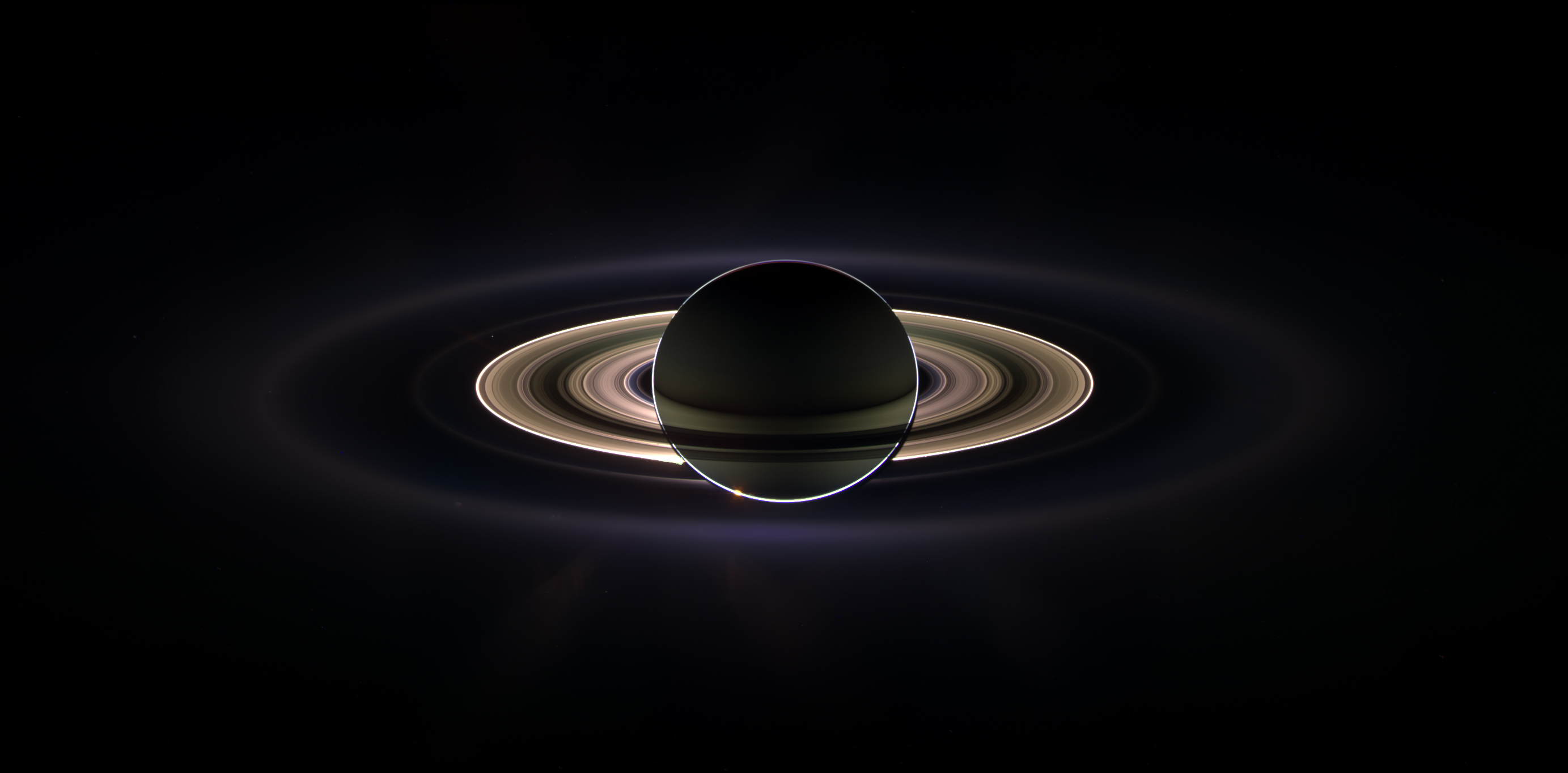

My wife @EstelleDeau is an astrophysicist, and as part of her job, she uses IDL to process heaps of data (mainly sent by the Cassini spacecraft, but also from other sources).

Why IDL? Mainly for historical reasons. When you advance in your carreer as a scientist in a very specialized field, you build your own toolkit to analyze data, fit it to various models, graph it in nifty ways, etc.; and often, this is a very specialized toolkit. If you’re bored or curious, have a look at the tech specs for ISS data (I mean, it’s just 171 pages). I can understand that if someone wrote that kind of code in a language, they wouldn’t want to rewrite it in another. So, here we are, with IDL.

This picture was assembled from a mosaic of smaller pictures, taken by a 1 megapixel, grayscale digital camera, moving at thousands of mph around Saturn. Told you: SCIENCE!.

Why function pointers?

It started with a simple idea: a lot of this IDL code had endless sequences of “if i EQ 1 then … else if i EQ 2 then … else …”, and I wanted to apply some classic refactoring:

- put each code section in its own function,

- replace the long sequence of if/then/else with an array of function pointers.

Let’s dive into IDL

The “workbench” looks like your average Eclipse-like IDE, with its load of quirks and fails. For instance, you have a button to build, and another to run; when run, it will first try to build, but if the build fails, it will run the old version. Also, the keyboard shortcuts (on a Mac) for those actions are Cmd+F8 and Cmd+Shift+F8. Since F8 requires Fn+F8, you end up pressing Cmd+Shift+Fn+F8. I’m comfortable with 7th and 9th chords on a piano so I won’t mind, but most people will probably use the mouse.

It looks like IDL is half-compiled, half-interpreted; i.e. while it requires a compilation phase, a lot of checking (and therefore, potential errors) happen at run time, which is quite surprising; as in “seriously, couldn’t you catch that at compile time?”

That being said, the online documentation of IDL is actually useful, once you know what to look for.

What does IDL look like?

Like this:

function mult,a,b

return,a*b

end

pro main_prog

print,mult(2,4)

end

This display 8.

The syntax is definitely weird, but makes sense if you think about the

fact that IDL was born before the 80s, and was inspired by Fortran.

You will often see UPPERCASE_NAMES(LIKE_THIS) and some /FLAG_NAMES

which betray it’s VMS heritage (where do you think MS-DOS got that crap

from?).

Do we have pointers?

IDL has pointers; the equivalent of &schmoo is

PTR_NEW(schmoo) (you don’t really have to use uppercase names,

but it helps to get into the atmosphere). However, if you try

ptr_new(mult) when mult is a function, you will have a very bad time.

It works, but when you try to actually reference the pointer, it will crash.

So, no function pointers.

When you don’t have function pointers, plan B is to evaluate arbitrary code. After looking around, I see that we have EXECUTE to do exactly that. And the doc here gets really helpful, since it mentions:

The EXECUTE function compiles and executes one or more IDL statements contained in a string at run-time. EXECUTE is limited by two factors: The need to compile the string at runtime makes EXECUTE inefficient in terms of speed. The EXECUTE function cannot be used in code that runs in the IDL Virtual Machine. Use of the EXECUTE function is not permitted when IDL is in Virtual Machine mode. The CALL_FUNCTION, CALL_METHOD, and CALL_PROCEDURE routines do not share this limitation; in many cases, uses of EXECUTE can be replaced with calls to these routines.

And, sure enough, you can do this:

result = call_function("mult", 3, 4)

We could declare an array of strings, containing the names of the function we need to call; but let’s keep looking a bit.

Structures

IDL has an interesting data type: structures.

At first, they look like structs, or maybe hash tables:

my_struct = {x: 42, y: 60, z: -1, color: "red"}

But they are ordered as well. You can access my_struct.x with

my_struct.(0).

Also, there is a kind of inheritance system:

my_new_struct = {my_struct, background: "black"}

I think it is better to think of structures as “annotated arrays”, i.e. regular arrays that come with a convenient label for each position, rather than real dictionaries. And, sure enough, there is a tag_names function that returns an ordered array of all the tags/labels/fields of your structure.

I looked for the equivalent for Python’s getattr, but it looks

like it doesn’t exist; however, I found a StackOverflow answer

which helped me to write it:

function getattr,struct,attr

tnames = tag_names(struct)

tindex = where(strcmp(tnames, attr) EQ 1)

if tindex EQ -1 then begin

print,"NOT FOUND: ",attr

;EXIT?

endif

return,struct.(tindex)

end

I haven’t figured yet how to raise an exception or properly halt

the program. EXIT crashed the workbench (we had to exit and restart

it). There was probably some magic button that we could have pressed

to restore it to working condition, but we couldn’t find it :-)

Putting everything together

In this example, we have a number of functions that need to be called in order, with specific parameters.

function job_foo,a,b

print,"doing job foo",a,b

return 42

end

function job_bar,a,b

print,"doing job bar",a,b

return 105

end

pro run_all_jobs

jobs = {$

job_foo: {a: 42, b: 4},$

job_bar: {a: 10, b: 5} $

}

jobnames = tag_names(jobs)

for i=0,n_tags(jobs)-1 do begin

jobname = jobnames(i)

job = jobs.(i)

print,"Starting job ",jobname

r = call_function(jobname, job.a, job.b)

print,"Result of job: ",r

endfor

end

As shown above, statements can span over multiple lines, by using $ at the end of the line. In the 70s, backslashes were a hipster thing.

And here, we prompt the user for the specific job they need to run:

pro run_one_jobs

jobs = {$

job_foo: {a: 42, b: 4},$

job_bar: {a: 10, b: 5} $

}

jobnames = tag_names(jobs)

print,"Which job should we run?"

print jobnames

jobname = ""

read,">>> ",jobname

job = getattr(jobs, jobname)

print,"Starting job ",jobname

r = call_function(jobname, job.a, job.b)

print,"Result of job: ",r

end

Another interesting fact: if you don’t do jobname = "", IDL will assume

by default that it is a number, and read will complain that the thing

you have entered doesn’t parse as a number.

Conclusions

If, as a professional programmer, IDL gives you heartburns, you can soothe the pain by watching this breathtaking video made with images taken by Cassini ISS cameras! :-)

If you know IDL and know better ways to do what has been shown here, I would be very happy to hear about it. Thank you!