I recently decided to check how much it would cost to offset the carbon footprint of my air travel. It was cheaper than I thought: for about 170 flights, it was about $1000. Here are some details and thoughts about the process.

A little bit of background

Since my move to the US in 2011, I’ve been flying a lot. Flights to Europe for vacations and holidays; domestic flights in the US when I was in a long distance relationship; and then my career evolved, as I became Docker’s first developer advocate. Between 2013 and 2018, I spent roughly 50% of my time at home, and the rest of the time traveling to conferences, meetings, and the odd vacation.

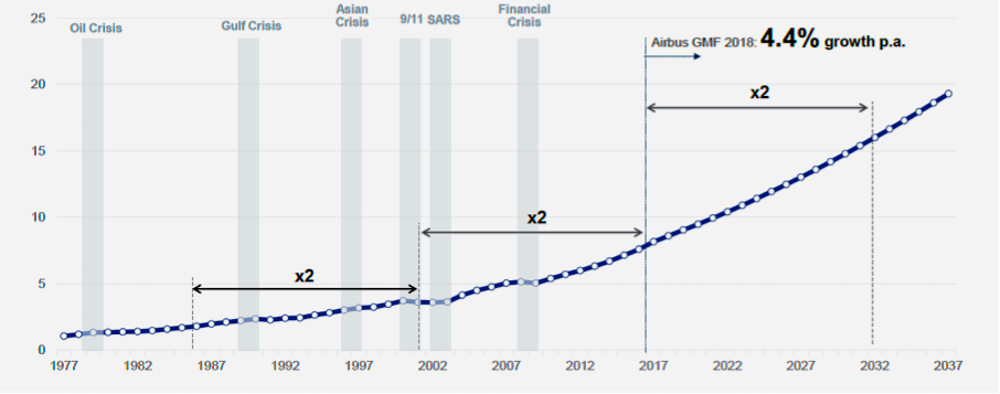

Climate change is real, and the environmental impact of aviation accounts for about 2-3% of all human-induced CO2 emissions. We won’t prevent catastrophic global warming just by cutting air travel; but it’s one of the things that has been growing significantly over the last decades.

In fact, it follows an exponential growth, except during periods of crisis. The graph below is from 2017, so it obviously doesn’t show the effects of the 2020 pandemic; but you still get the general idea:

Source: TSEconomist.

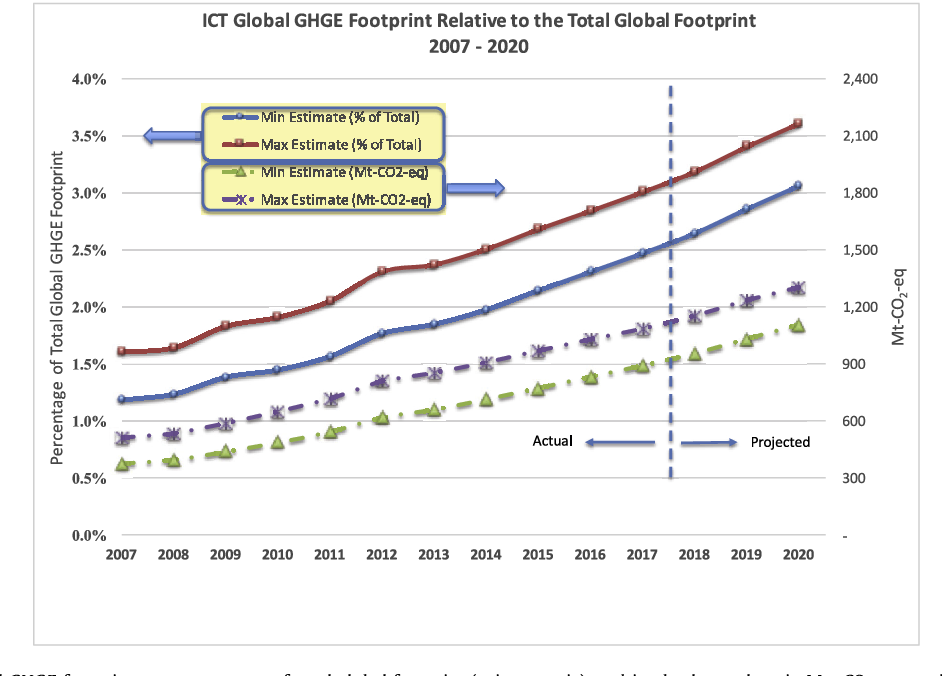

Another thing that has been growing significantly is computing. Virtually insignificant a few decades ago, it now accounts for 2-3% of our CO2 emissions as well. And just like air travel, its growth follows an exponential curve.

Source: Belkhir, Elmeligi, 2018.

So, there would also be a few things to say about “green computing,” but let’s stick to air travel for today.

What’s the idea behind carbon offsets?

When we burn fossil fuels (like coal, gas, oil), the combustion releases CO2 in the atmosphere. That CO2 is a greenhouse gas, and it’s directly responsible for the extremely rapid temperature elevations that we’re witnessing.

Carbon offsets are projects to reduce CO2 (or other greenhouse gases). There are many ways to do that. One strategy is to reduce CO2 emissions, for instance by replacing a source of energy that generates a lot of CO2 with another source generating less CO2. Example: if you keep your house warm by burning fuel, I could incentivize you to install a heat pump or other efficient heating system that will give you the same temperature inside, but generate less CO2. Another strategy is to plant trees: trees absorb CO2 from the air and turn it into carbon (a tree is about 50% carbon, in mass). Estimates tell us that a tree captures about 48 pounds of CO2 per year. In 2017, worldwide CO2 emissions added up to 36 billion tonnes. So to compensate for worldwide CO2 emissions, we “just” have to plant 1.5 trillion trees. Easy!

Some folks think that we can plant a trillion trees. Other folks think that it’s actually pretty hard, and even if we do it:

- we have to keep planting trees as our CO2 emissions increase year over year;

- we have to make sure that these trees stay in place (don’t get cut, don’t burn because there are more forest fires, etc).

We won’t solve global warming (or even just the carbon aspect of it) with a single solution. It’s likely that we will have to fly less planes, drive less cars, plant more trees, use better sources of electricity, keep our phones, computers, and other devices longer, and many other things.

That being said, what’s the process for applying carbon offsets to air travel?

Measuring our individual impact

The International Civil Association Organization (ICAO) has created a calculator to estimate how much CO2 can be attributed to a single trip. The general idea is to estimate how much fuel was burned by the plane for that flight, how much of it can be attributed to passenger travel (versus, say, freight transport), divide by the number of passengers, and multiply by 3.16 (because burning 1 tonne of aviation fuel generates 3.16 tonnes of CO2). There are some minor adjustments that are detailed in the ICAO methodology, but that’s the general idea.

There are many sites that offer more-or-less easy-to-use calculators where you can enter a specific flight information, and that give you the option to fund a carbon offset project to match the emissions of that specific flight.

So, in theory, all I had to do was to find one of these sites, enter my flight data, and enter my credit card number.

Practical details

There were, however, two details that I needed to address.

First, finding a reputable organization. Since many carbon offset programs finance actions that are in another part of the globe, you generally can’t just go and check for yourself that they’re actually planting trees or doing whatever they promised to do. This is true for many other markets, of course; but I don’t know if there is a trustable certification system for consumer-oriented carbon offset programs

Next, I had about 170 flights over 5 years (2015-2019). I was keeping track of the time I was spending in and out of the US for immigration reasons, so I already had a spreadsheet with almost every single flight during that period: departure airport, arrival airport, and date. I spent a few hours adding missing flights (domestic flights and flights not bound to or from the US) as well as the class of travel (economy except for a couple of upgrades). But thinking about manually entering that data on a website felt daunting. (Especially because I felt there had to be an easier way!)

Project Wren

Both challenges were solved when I saw someone I trusted endorse Project Wren. First, I appreciated that Wren gives us a way to estimate our carbon footprint depending on our lifestyle (where we live, what we eat, etc). They also offered multiple kinds of carbon offsets. And they had a flight calculator.

Alright, so I found the right “vehicle,” but I was still dreading entering all my flights manually. I was considering reimplementing the ICAO formula myself to compute my carbon footprint, and making a financial contribution of that amount. But before I could follow through on that plan, I was contacted by one of the co-founders of Wren, checking in to know if I needed help with my project (I had left my email address when creating a profile on Wren). During a short email exchange, I explained what I was trying to do, shared that spreadsheet, and got it back annotated with the CO2 equivalent and offset cost for each flight.

Results and thoughts

The numbers were astonishingly low. To offset my 200 flights, It barely cost me $1000. Domestic flights were a few bucks each, and long distance travel (say, Europe-US) $15-20 each.

I found this both encouraging… and depressing.

Encouraging, because it means that these offsets are relatively easy. I was expecting something much higher, and I thought that I would have to make a more difficult choice. But paying $1000 for five years flying almost every week… felt like the least I could do. Of course, $1000 is a lot of money for many folks; but let’s be honest: if you can afford to travel that much, you can most likely afford the offset.

Depressing, precisely because it means that we could offset the carbon emissions of all plane travel by raising the price by peanuts. (One percent, maybe?) For domestic travel, the carbon offset would cost less than a coffee (and definitely less than a coffee at the airport or in the plane).

Of course, offsets are not a magic solution. They are but one of the many things that we need to do to tackle climate change. It turns out that they’re easier and cheaper than I thought, even given my specific profile.

Let’s be clear: I don’t consider these cheap carbon offsets as a free pass to fly around in as many planes as I want, as long as I offset the associated CO2 emissions. We need a holistic approach. During the last few years, I’ve flown significantly less. My main source of income is now my Docker and Kubernetes training courses. As a freelancer, I have more freedom about how I organize my work. I group my customer engagements so that I cross the Atlantic less often. Sometimes I lose a customer who wants me to fly “right there right now” and doesn’t want to wait. Well, so be it.

Within Europe, I take the train when it’s feasible, even if it’s sometimes a bit longer, and often more expensive. I have the privilege of having a job that lets me work from home (when I don’t travel), so I don’t commute and don’t own a car. Even with these efforts, there is still enough air travel to have a “carbon footprint” that is far worse than the average European, and even the average American. So I need to continue to improve that; and to keep looking at other options too.

Offsetting more than air travel

Project Wren isn’t limited to air travel. They can also compute someone’s average carbon footprint depending on where they live, the size of their house, what they eat, how they move around, and many other factors. It’s based on statistics and averages, of course, but it’s still very useful.

And when purchasing a carbon offset, you get the option of picking exactly how you want that offset to happen, i.e. to what kind of initiative the money will go to.

I encourage you to have a look at Project Wren, or at any other similar project, if only to get an idea of your carbon footprint. If you can finance a carbon offset project or reduce your carbon footprint in other ways, that’s fantastic, but my goal here was just to share my experience with one specific aspect of the battle that we’re fighting against climate change. Thanks for reading!